By: Karissa Courtney

Background

If you have lived in Boulder for any amount of time, the topic of water will always be one to come up. Whether you are trying to go swimming and can’t find many places to go, your morning walks take you along the small creeks, or you have to figure out how to get water to your farm, you will notice that water is pretty scarce.

Boulder is considered a high desert or high plains area, a vague term basically meaning that the area is relatively dry and at a high elevation of 4,000ft – 6,000ft. In general, Colorado’s combination of high elevation, mid-latitude, and middle of the continent position results in a dry climate with very low humidity. Besides the high elevation, Colorado’s distance from the oceans is a key element resulting in dryness. Storms from the Pacific Ocean moving eastward lose most of their moisture on the mountaintops and west-facing slopes[i] (80% of Colorado’s precipitation falls on the west side of the Continental Divide)[ii], which means that east-facing slopes (Boulder!) receive very little of these water deposits. The Front Range also has very few naturally occurring lakes, which doesn’t help our water problem.

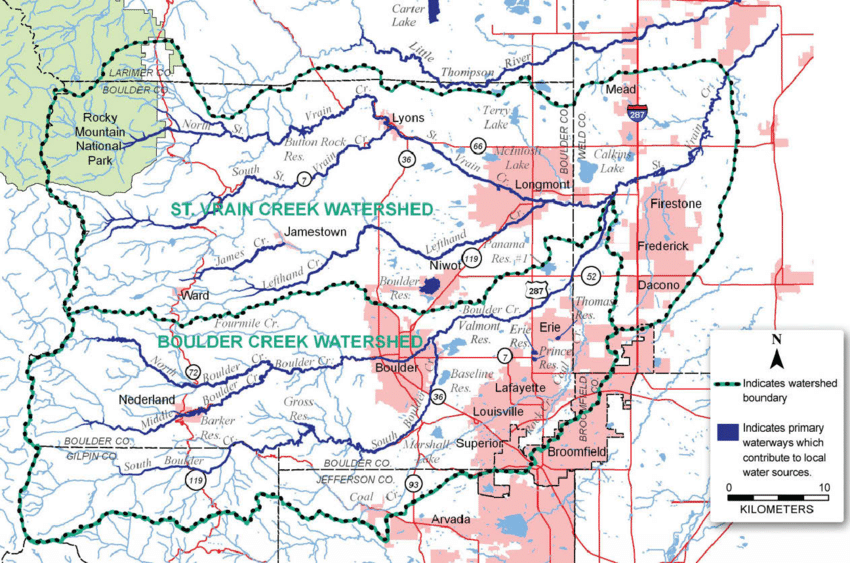

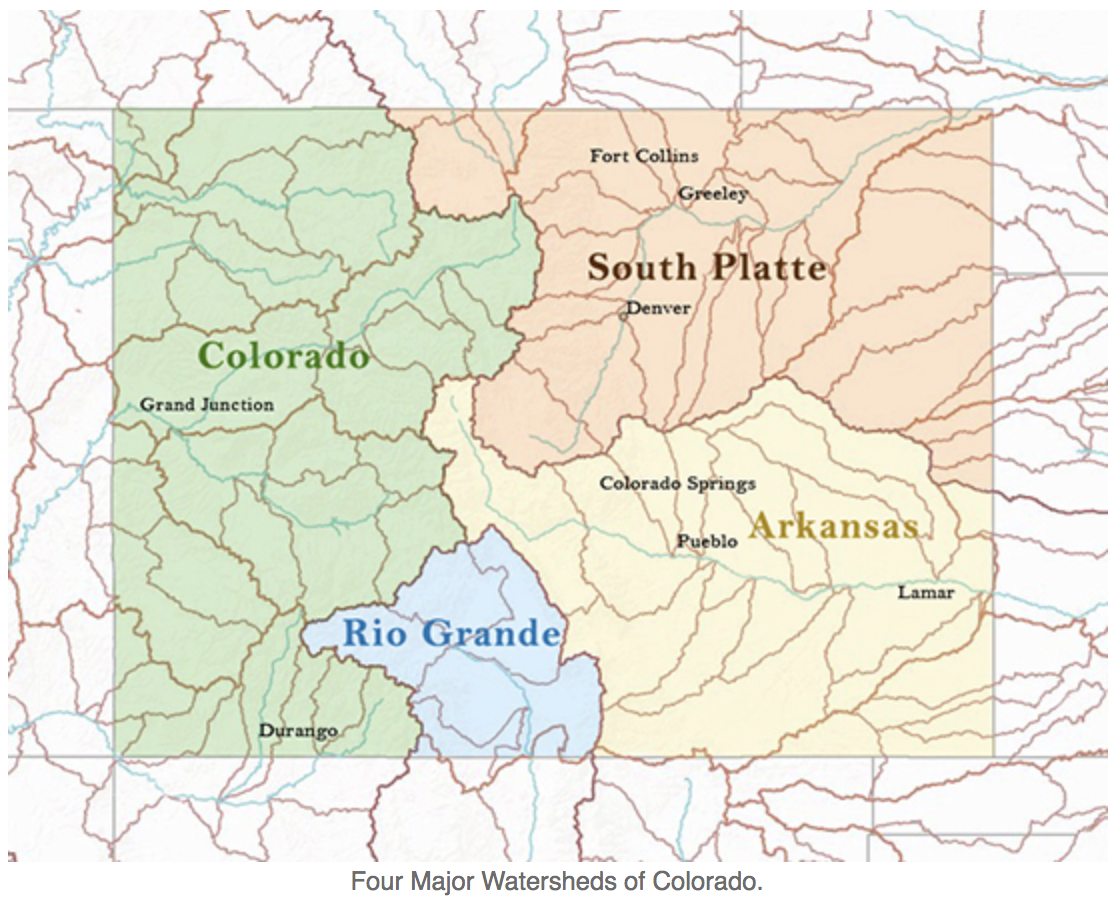

So where does our water come from? Primarily snow melt that fills streams and travels down to the Boulder Valley. There are two main watersheds in the area: the St. Vrain Creek Watershed, which includes Left Hand Creek and St. Vrain Creek, as well as the Boulder Creek Watershed – which includes Coal Creek, South Boulder Creek, and Boulder Creek. Both of these watersheds are part of the larger South Platte River Basin, the tributary of the Missouri River.[iii]

(From Research Gate: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Boulder-County-Watershed-Map_fig1_317157021)

(From Colorado State University Surface Water Resources: https://waterknowledge.colostate.edu/hydrology/surface-water-resources/)

The history of water in Boulder is long and confusing one. Since the first settlers arrived in the area, water has been a problem that has needed to be addressed. The first Anglo settlers arrived in Boulder in 1858, and only a year later, the first rights to divert water from Boulder Creek and South Boulder Creek were established. This led to the common law, “First in time; First in right.”[iv] Ever heard of it? This first-come-first served rule became the norm in 1862 when it was affirmed by the Colorado Territorial Legislature. This meant that water rights went to the person who used/claimed the water first, not to whoever owned land next to that body of water. Two years later and there were already 23 ditch companies that had water rights claims to the Boulder Creek. [v] The Prior Appropriation Doctrine further outlines this agreement, as it was developed to respond to the arid conditions of the west since water sources aren’t where they are needed. Rights are thus restricted to quantity, timing, place and purpose (Read more HERE). In order to obtain a water right, one must show:

- Their intent to appropriate

- Beneficial use

- Enact no injury – existing water rights holders are entitled to the maintenance of the same stream conditions (quantity, timing, quality) as existed at the time of their appropriation.

These decrees remain in effect until either a change is sought, or if the water right is abandoned. Rights are sold with property and passed down to children. There are two different types of water rights: 1) Direct Flow, which is measured in terms of a flow rate, not total volume, and 2) Storage, which is measured in terms of volume (in acre-feet) and is usually only for one filling of the storage vessel per year, like a reservoir.[vi]

The Colorado Supreme Court Case, Coffin vs. Left Hand Ditch Company was a case that upheld the “First in time, First in Right” usage. In 1863, the Left Hand Ditch Company built a dam across the St. Vrain Creek in order to divert water into the James Creek. Reuben Coffin and his brother had owned land along the St. Vrain Creek since 1866, but they had never declared their water usage. Later, in 1867, the St. Vrain Creek ran dry and Coffin and other farmers went upstream to dismantle the dam that the ditch company had built. The company then rebuilt the dam and Coffin sued. The court ruled that Left Hand Ditch Company’s right to divert water was superior to Coffin’s proximity to the creek.[vii]

This brings up the question of what a ditch company actually does. Shareholders are entitled to the delivery of a portion of the ditch’s water based on the number of shared owned. Often, the ditch company is responsible for the delivery of water to the headgates. Boulder County, today, actually owns shares in 98 ditches, owning more water than any other open space agency in Colorado. Most of this water is dedicated to agricultural production, wells, and reservoirs/ponds.

The Beginnings of Boulder’s Water System

Boulder’s population has been continually growing since its inception, and with that growth came the problem of storing and keeping enough water in the area. Much of Boulder’s history involves the continual growth and building of reservoirs, ditches, and water diversions.

In 1875, construction began on the Boulder Ditch and Boulder Reservoir (also known as Red Rocks Reservoir and Sunshine Reservoir No. 1). The headgate was on the north bank of Boulder Creek at the mouth of Boulder Canyon. Back in this time, residents would get their water at the public square downtown. A diversion was built in 1877 between Boulder Creek and downtown Boulder so the rain and melted snow runoff could flow back into the stream. In 1882, water rights were formally declared by the Boulder County District Court and over 98 ditch companies were granted priority rights. Silver Lake Reservoir was built in 1887 at the headwaters of North Boulder Creek (near Nederland), just below the Continental Divide. A year later, the Silver Lake Ditch and Reservoir Company was formed to deliver water down to the greater Boulder area (later, in 1920 Boulder closed all the Silver Lake Watershed land to public access). In 1893, the Sunshine Reservoir No. 2 was finished and the intake was near the intersection of Four Mile and Boulder Creeks. Chautauqua Park opened in 1898, and with it, the need for yet another city reservoir, which was built the same year. Water for this reservoir came from a ditch in Gregory Canyon and pipes in Boulder Canyon. Later, a second Chautauqua Reservoir was finished in 1922. (These were later filled in). Around the same time as the first Chautauqua Reservoir, the city also enlarged Goose Lake by raising the dam.[viii]

The Boulder District Court, in 1907, finally recognized reservoir storage rights for the first time and the City was allotted a 20-cubic-feet-per-second direct-flow for the Boulder City Pipeline. A few years later, in 1910, the Barker Dam was finished on Barker Reservoir near Nederland, increasing the storage capacity. [ix]

Colorado Big Thompson Project

Then, in the late 1930s, farmers, ranchers, and cities in northern Colorado joined with the United States Bureau of Reclamation to form the Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District, which has hopes for a large diversion of water from the Western Slope over to the Eastern Slope. This led to the Colorado Big Thompson Project, which became a tunnel under the Continental Divide, bringing water to the Front Range from the Western Slope.[x] It was undergoing construction from 1938-1957, and in 1947 the first water was carried through out to the Big Thompson River and the plains. However, Boulder didn’t join in until 1953. This project now encompasses 12 reservoirs, 6 power plants, 95 miles of canals, and 35 miles of underground tunnels, and now serves around 860,000 people.[xi] This is basically how so many people are able to live in the Front Range. In the early 1950s, Boulder Reservoir was built, in order to take part in the Colorado Big Thompson Project.

Pollution and Water Quality Issues

by Karissa Courtney

Since the beginning of Boulder, there have been water quality issues. In 1877, to try to help with clouding water from the mills and mines, the first water protection ordinance was passed, but failed to mention those actions that were most adding to the problem, “No person shall put any carcass or filthy animal or vegetable matter into the reservoir, nor shall any person bathe or swim therein or skate upon the ice which may form thereon in cold weather.” (Fred A. Fair Engineering Association, Water Rights of the City of Boulder, Colorado, Report to E. O. Heinrich, City Manager (Boulder: 1919) Appendix B, 7). [xii]

Still, a few years later in 1883, dead horses were found in the creek and after the water was turned back on, a local physician suggested that households filter their drinking water by using a formula of alum and soda. In 1900, tungsten was identified in the water, making the quality very bad at the mouth of Boulder Canyon and Nederland. To combat that, six years later the intake pipeline was moved upstream on North Boulder Creek. Additionally, by 1920, all Silver Lake Watershed land was closed to public access to help with the water quality. [xiii]

Then, in 1959, a new organization formed, called PLAN-Boulder, with the goal to slow down growth and protect special qualities of the Boulder area. They drew an imaginary boundary, the “blue line” where no city water or sewer services could be extended. In 1961, an exception was made for the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) building site (above their 5,750ft elevation line). Then about 10 years later, the first water treatment plant was in operation using fluoridation, the Betasso Water Treatment Plant, located in the mountains west of Boulder. At around the same time, the Boulder Reservoir Water Treatment Plant also began operations. Then in 1974, President Ford signed the Safe Drinking Water Act, giving state health departments and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) the authority to monitor and regulate the drinking water. This act also required the testing for bacteria, radiological contamination, inorganic chemicals, and pesticides. In 1973, Senate Bill 97, at the action of the Colorado Water Conservation Board, gave the legal right to acquire water rights to use to preserve the natural riparian environments. [xiv]

- Betasso Treatment Process

- Coagulation: step 1 – forming clumps of particles known as floc. Coagulant chemicals used are Alum blended with Sumaclear (polyaluminum chloride)

- Flocculation: allow the floc particles to grow using slow mixing in order to remove suspended solids

- Sedimentation: clear water spills off the top of the basins and residuals settle to the bottom where it is scraped out

- Filtration: using beds of fine sand and anthracite. Water drains through the filter beds for 48-60 hours

- Fluoridation: adding liquid fluoride to a level that reduces tooth decay

- Disinfection: kills pathogens using chlorine

- Stabilization: adjusts alkalinity and pH (to 7.8) through lime and carbon-dioxide

- Distribution [xv]

Water Conservation Today

Due to the issues of the past, and those that we currently face, Boulder follows many guidelines, plans, and advisory boards to ensure that our water is protected and used in the best possible ways.

By Karissa Courtney

- The Boulder Valley Comprehensive Plan, Section 3.26 specifically discusses the protection of water quality in the area. They say, “The city and county will continue to reduce point and nonpoint sources of pollutants, protect and restore natural water systems and conserve water resources,” placing special emphasis on watershed planning and pollution prevention. Additionally, in Section 3.29, they mention expanding the in-stream flow program of the Boulder Creek watershed, which protects the riparian and aquatic ecosystems.

- Related to the Boulder Valley Comprehensive Plan, is the Environmental Resources Element Update, which modified the criteria for designating Cristial Wildlife Habitat (CWH) and specifically wetlands and riparian areas were added.

- Greenways Master Plan has a purpose stated as,

- “The Greenways Program will manage these areas so as to integrate the following objectives: 1) to protect and restore riparian, floodplain, and wetland habitat, 2) to enhance water quality, 3) to facilitate storm drainage and mitigate floods, 4) to provide alternative transportation routes or trails for pedestrians and bicycles, 5) to provide recreation opportunities, and 6) to protect cultural resources.” This plan follows the Boulder Valley Comprehensive Plan, the Comprehensive Flood and Stormwater Utility Master Plan, the Transportation Master Plan, Parks and Recreation Master Plan, the Water Quality Strategic Plan, and other community and stream specific plans.

- Grasslands Ecosystem Management Plan: Wetlands. Here they state, “because Wetlands support both aquatic and terrestrial plant and animal species, they contain a disproportionately high level of biodiversity relative to other ecosystems,” however, “despite their many values, most wetlands in the Boulder Valley have been significantly degraded or destroyed by land use practices…In recognition of their functions and values, and the significant conservation issues facing wetlands, Boulder has adopted a wetland protection program…”

- Water Utility Master Plan outlines The City of Boulder’s Water Utilities responsibilities. These include: “managing, storing, treating, monitoring, and delivering safe, potable water to the citizens of Boulder…as well as manage[s] related environmental programs such as the Boulder Creek Instream Flow Program.”

- Source Water Protection Plan: The city’s Source Water Protection Area has three zones and its goals are to:

- “engage key land and resource managers in the SWPP development process and create an awareness of the community’s drinking water sources and susceptibility to surface water quality;”

- “identify and prioritize existing and potential water quality impacts to the drinking water supplies;

- “serve as a guide for implementing best management practices to more effectively and efficiently allocate resources towards watershed protection activities; and”

- “update the city’s internal contingency plan, which lays out a coordinated approach for responding rapidly, effectively and efficiently to any emergency incident that threatens or disturbs the community water supply.”

- City of Boulder Resilience Strategy mentions Boulder’s Water Resources, “Investing in both source water protection and enhancing water infrastructure continue to be of chief importance to the city. This has included investments that secure additional capacity and redundancy at the city’s water treatment facilities which help reduce risk from drought and other concerns. It also includes a long history of investing in the city’s stormwater and wastewater systems which help mitigate flooding and sewer back-ups.”

- 2019 Annual Report: Water Conservation Impact, City of Boulder: This Water Conservation Group consists of 30 people who are “determined to make conservation so simple that you don’t even realize you’re doing it.” They are “an innovative nonprofit with programs that help people save water, reduce waste, and conserve energy.”

If you are interested in being a part of water resource decisions, check out the Water Resources Advisory Board!

References

- 2019 Annual Report: Water Conservation Impact, City of Boulder

- Boulder County Parks and Open Space’s Chris Williams (speaker)

- Boulder Valley Comprehensive Plan: 2015 Major Update, Adopted 2017

- Boulder’s Waterworks Past and Present: Silvia Pettem and Carol Ellinghouse, 2014

- Climate of Colorado by Colorado State University

- City of Boulder Resilience Strategy, 2017

- City of Boulder Source Water Protection Plan, 2017

- Environmental Resources Element – Comprehensive Plan

- Grasslands Ecosystem Management Plan: City of Boulder OSMP, 2010

- Greenways Master Plan: City of Boulder, 2011

- Water Utility Master Plan Executive Summary: City of Boulder, 2011

[i] Climate of Colorado by Colorado State University

[ii] Boulder County Parks and Open Space’s Chris Williams (speaker)

[iii] Boulder County Parks and Open Space’s Chris Williams (speaker)

[iv] Boulder’s Waterworks Past and Present

[v] Boulder’s Waterworks Past and Present

[vi] Boulder County Parks and Open Space’s Chris Williams (speaker)

[vii] Boulder’s Waterworks Past and Present

[viii] Boulder’s Waterworks Past and Present

[ix] Boulder’s Waterworks Past and Present

[x] Boulder County Parks and Open Space’s Chris Williams (speaker)

[xi] Boulder’s Waterworks Past and Present

[xii] Boulder’s Waterworks Past and Present

[xiii] Boulder’s Waterworks Past and Present

[xiv] Boulder’s Waterworks Past and Present

[xv] Boulder’s Waterworks Past and Present